Learn About the Art > About Old Pawn Jewelry > Fred Harvey Jewelry

About Fred Harvey Jewelry

To View Current Fred Harvey Era Bracelets - click HERE

Background:

Near the end of the 19th century, and through to 1930, the tourist trade in the Southwest saw considerable growth. Indian-made jewelry was one of the more popular commodities that the Anglo tourist purchased and brought back home, as it was a wearable token of their travels and of their experiences in the Southwest. However, as traders quickly realized, the Anglo taste in jewelry differed greatly from that of the Native Americans, such as the Navajo Indians. Whereas the Navajo would appreciate heavier, "bulkier" pieces (for example, thicker, larger Sterling Silver bracelets, rings, and necklaces with large turquoise stone settings), the Anglo tourist (and Anglo women in particular) would prefer lightweight examples with smaller elements of ornamentation and stones.

Once Indian jewelers and traders realized the Anglo preference, they began catering to the Anglo tourist's tastes by producing a full line of lightweight jewelry, much of it mass-produced with the help of specialized machinery and commercial sheet silver. In addition to the consideration of weight, various design elements or symbols were decided upon as standard designs that would decorate most products - the Thunderbird, the arrows (crossed arrows or single arrows), the four-directions symbol, lightning zigzags, arrowheads, etc. It was perceived that these were the symbols that most tourists had in mind as belonging to the Indian realm, and consequently, many Indian jewelers would keep to the use of these symbols instead of adding their own personal touch or incorporating other aesthetics.

It is important to note, however, that while much of the jewelry was produced with the aid of specialized machinery, there were also many jewelers who made fine pieces completely by hand, who would not use the commercial sheet silver and machine-drawn silver rods but rather hand-cut Sterling silver pieces from a block of silver that was hand-hammered (or from a Mexican peso), then spend the time to file, stamp and polish their work. These handmade pieces were the ones that the Anglo tourist would intrinsically prefer (as the whole point was to bring back something handmade by an Indian from the "Wild West"), but they would also cost much more than the machine-cast examples. The differences in price and quality led to some confusion in the market, and some frustration with Anglo customers. It was difficult to tell which pieces had been made by hand and which had been made mostly by machinery.

"Fred Harvey Jewelry"

When one refers to "Fred Harvey era" jewelry, one is generally speaking about this genre of lightweight and mass-produced jewelry that was made for sale to the Anglo tourist along the Santa Fe railroad lines, in hotels and retail shops run primarily by the Fred Harvey Company. The name, Fred Harvey, is a quite famous one in Southwestern history. Below is a brief discussion on Fred Harvey, the entrepreneur.

Background:

Near the end of the 19th century, and through to 1930, the tourist trade in the Southwest saw considerable growth. Indian-made jewelry was one of the more popular commodities that the Anglo tourist purchased and brought back home, as it was a wearable token of their travels and of their experiences in the Southwest. However, as traders quickly realized, the Anglo taste in jewelry differed greatly from that of the Native Americans, such as the Navajo Indians. Whereas the Navajo would appreciate heavier, "bulkier" pieces (for example, thicker, larger Sterling Silver bracelets, rings, and necklaces with large turquoise stone settings), the Anglo tourist (and Anglo women in particular) would prefer lightweight examples with smaller elements of ornamentation and stones.

Once Indian jewelers and traders realized the Anglo preference, they began catering to the Anglo tourist's tastes by producing a full line of lightweight jewelry, much of it mass-produced with the help of specialized machinery and commercial sheet silver. In addition to the consideration of weight, various design elements or symbols were decided upon as standard designs that would decorate most products - the Thunderbird, the arrows (crossed arrows or single arrows), the four-directions symbol, lightning zigzags, arrowheads, etc. It was perceived that these were the symbols that most tourists had in mind as belonging to the Indian realm, and consequently, many Indian jewelers would keep to the use of these symbols instead of adding their own personal touch or incorporating other aesthetics.

It is important to note, however, that while much of the jewelry was produced with the aid of specialized machinery, there were also many jewelers who made fine pieces completely by hand, who would not use the commercial sheet silver and machine-drawn silver rods but rather hand-cut Sterling silver pieces from a block of silver that was hand-hammered (or from a Mexican peso), then spend the time to file, stamp and polish their work. These handmade pieces were the ones that the Anglo tourist would intrinsically prefer (as the whole point was to bring back something handmade by an Indian from the "Wild West"), but they would also cost much more than the machine-cast examples. The differences in price and quality led to some confusion in the market, and some frustration with Anglo customers. It was difficult to tell which pieces had been made by hand and which had been made mostly by machinery.

"Fred Harvey Jewelry"

When one refers to "Fred Harvey era" jewelry, one is generally speaking about this genre of lightweight and mass-produced jewelry that was made for sale to the Anglo tourist along the Santa Fe railroad lines, in hotels and retail shops run primarily by the Fred Harvey Company. The name, Fred Harvey, is a quite famous one in Southwestern history. Below is a brief discussion on Fred Harvey, the entrepreneur.

|

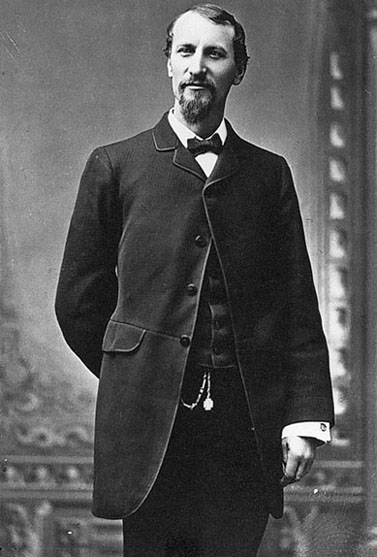

In 1876, Fred Harvey (1835–1901) struck a deal with Charles Morse at the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad company, permitting Harvey to establish eating houses along the railroad lines, free of charge. At these "Harvey Houses," wealthy and middle-class Anglo tourists would stop for rest and delicious food as they traveled deeper into the "Wild West." In addition to the houses, Harvey also struck a deal to serve food inside the train cabins themselves, providing another source of income for his company.

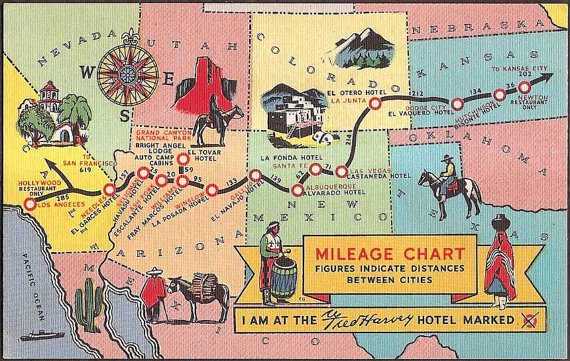

Harvey passed on in 1901, leaving The Fred Harvey Company to his sons. Cultural tourism gained traction in the region, and more hotels were built to accommodate the increase in tourists. The Fred Harvey Company ran Harvey Houses (restaurants) and hotels alike. Once the automobile became a more common way to travel (especially after World War I), there was a considerable decline in the number of train passengers. To adjust to the new tourist demographic, Fred Harvey Company developed new attractions and services. They began to market the lifetsyles of the Native Americans of the Southwest, staging "Indian Detours," or scenes of Native American living in the desert (viewable only by purchase of admission). Indian arts and crafts were also marketed and sold to the tourist (in our case, for example, "Fred Harvey jewelry" sold at the various locations run by the company). |

Today, Fred Harvey era jewelry is widely collected and sought after. Easy to wear, and generally with a fair amount of ornamentation/stamping, Fred Harvey jewelry is an enjoyable genre of Indian jewelry that takes us back 100 years and can leave us wondering, "how would I have felt if I purchased this item along the Santa Fe railroad in 1910? What would my life have looked like, back then?"

Comparing Navajo bracelets 1870-1930

|

|

The items below are available for purchase through our gallery. Please contact us with any questions: (949) 813-7202.